Before explaining the myriads of potential security advantages that Free, Open Source Software (FOSS) may or may not have, let’s first ask the question you came here for: “Is Free, Open Source Software [always] more secure than proprietary software?”

Of course, the answer to that question is: “It depends”. Software can (and does!) contain bugs and security flaws, whether it is Open Source or proprietary. The difference between either option is of course, that FOSS projects can be audited easily and by everyone world wide, whether they are a hobby programmer or a software security company, while the source code of proprietary software is typically a case of business secrecy. [1, 2]

However, that begs the question whether the sole potential of being audited by thousands of people at all times (whether this actually happens or not) makes software more secure than proprietary software where the source code can not be seen by anyone, including potential attackers.

Is Open Source insecure? – No!

Free, Open Source Software (FOSS) is often times labeled as “nice idea, but unfit for critical infrastructure”, particularly by those not working in the field or by stakeholders of proprietary software companies. This notion was much more common a few years ago than it is today, but it is still fairly widespread until now.

As an example, in a Freedom of Information (FOI) request the German government was asked in 2017, why certain sections in German administrations would not use Open Source Software wherever possible. This was particularly the case for security and data critical administrative fields, like voting procedures, the military, official statistics and taxation. In most cases the answers follow the argument that it would likely make the software less secure if it was transparent and open. [2]

This argument is not new of course, but it seems to experience growing popularity every time a new security vulnerability appears in widespread Open Source software pieces. And understandably so, since many of the famous breaches we hear about in the media appear to affect such Open Source Software libraries, like OpenSSL’s Heartbleed bug in 2014, a massive privilege escalation in the Linux-Kernel in 2016 or the Log4Shell security vulnerability, just a few months ago.

So it is obvious that questions about the security of Free, Open Source Software come up frequently, especially because some fundamental concepts about today’s digital infrastructure as well as general IT security frameworks appear to be misunderstood in the public, where verifiably unsafe ideas like the dependence on “Security through Obscurity” still remain popular. Instead software security should first and foremost come from clean, intensively tested and broadly audited code as well as an coding and discussion environment with decent culture of failure and error management. [4, 5]

When is Open Source secure and when is it not?

It would be an incomplete statement to say that the license of a software project alone would make it inherently more secure. Again, as mentioned before: Any software has bugs and security vulnerabilities. The (theoretical) advantage that Free, Open Source Software has over proprietary solutions is the development culture behind such FOSS license.

Let us quickly explore, how code contributions typically work in Open Source projects: Usually, Open Source projects are more than happy to accept code from people outside of the core project team and have streamlined contribution guidelines exactly for this reason. They outline the steps to be taken when adding or modifying code such that the changes can be easily reviewed by the maintainer(s) of the project. Often times, the guidelines also include preferred coding styles, any cautions to be taken and how to apply automated testing to new modifications. As the code itself, such proposed changes are usually open for anyone to see and for anyone to join the discussion about. This creates room and a platform for exchange and improvement not only of the code base, but also for the skills of the (new) developers. [6]

Being completely out in the open fosters a culture of writing cleaner code and taking fewer easy shortcuts, which could potentially introduce attack surface. Additionally, “more eyes” on the code base has the potential for security issues and bugs in general to be resolved much quicker than would be the case if the software was developed in an opaque manner with only a handful of developers going through it at best. Similarly to privacy promises by those proprietary software vendors, one has to naively believe them about the security of their software too – in the case of Free Open Source Software, this is simply not the case as the code can be audited by third parties at any given time. It is no surprise, that many vendors of proprietary software, such as Google use an “Open Core” approach nowadays, basically capitalising on the advantages of Open Source Software (also regarding security), without contributing to the overall FOSS community. [7]

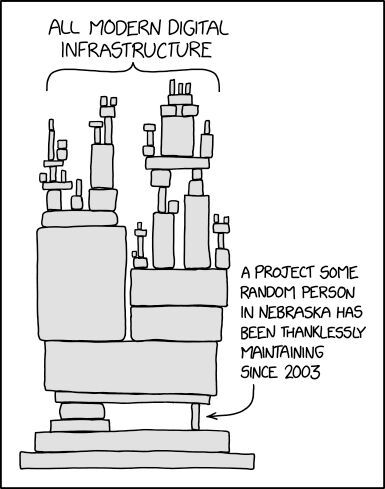

However, recent debates about the infamous Log4Shell security vulnerability brought up again a related problem of software supply chains. The issue describes the fact that much of our modern IT infrastructure, be it FOSS or proprietary heavily relies on software parts that not much people care about or contribute to. It basically removes the “many eyes” argument from the equation and leaves some seemingly random software libraries that only a small group or even a single developer works on for several decades in their free time, while giant commercial software projects rely on it without ever contributing or auditing it. For those that like visual representations, the XKCD 2347 comic strip summarises the issue precisely. [8]

Licensed under CC by-nc 2.5.

However, software supply chains are not an issue with Open Source specifically as pretty much all software today relies on a myriad of different professional as well as less maintained projects, particularly in the Web- and cloud based sphere. The supply chain issue is therefore more about making sure that all parts of a software project are well maintained and actively developed. This is again much more transparent if both the supply chain as well as the main project consist of Open Source projects. At least for FOSS project, there is the chance that users and third parties can openly and publicly report such issue and it is there for everyone to see how the project reacts to it. [8]

What does scientific research show?

The issue of software security has been broadly debated in scientific research for decades. Quite early on, the notion of the “Open Source paradigm for security through openness” qualified as a valid security model in software development in many cases. It confirmed the previous suspicions that software security could be improved whenever it was designed to be transparent, i.e. when the security procedures were designed to work even when everyone could understand them in detail. [9]

As a limitating factor, it is important to understand, that the opaque nature of proprietary software can also manifest in the disclosure of existing security vulnerabilities, meaning that while for Free Software projects, it is inevitable to make security vulnerabilities public, while proprietary software vendors may choose to patch them up quietly. Similarly, scientists acknowledged that transparency could only then lead to greater security if the community around such project would reach a critical mass where public audits are a reasonable scenario. [9, 10]

This problem particularly exists, because as with the rest of the development work within Open Source projects, the discovery and disclosure of security vulnerabilities often times happens out in the open as well. This gives attackers a potential time window to act quickly, for as long as the vulnerability is not fixed and (more importantly) before software users have applied appropriate security patches. Empirical research found, that while Open Source projects on average appear to have slightly fewer critical security issues, find those earlier and provide remedies for those much quicker than their proprietary counterparts, software users could potentially be at slightly higher risk if they do not apply security updates in due time – given the presumption that the knowledge about a security vulnerability gives attackers the opportunity to act on them, which is a controversial and still highly debated hypothesis. [11, 12]

As a remedy, many bigger Open Source projects have transitioned to (temporary) non-disclosure of vulnerabilities until appropriate security updates are made available, meaning that potential security issues are revealed only to an inner developer core team and made public as soon as remedies are available. Particularly with mission critical, commercial Open Source projects, customers are informed before the public in order to give them time to apply the security patches. [13]

Conclusion

The usage of Free Open Source Software opens up the potential for better development practices and higher over-all code quality as well as security. The arguments in favour of Open Source Security and against it are discussed in a heated environment and often times follow some sort of hype dynamic, claiming that either Open Source is inherently “bullet-proof” or is a complete security disaster respectively.

Of course, both notions do not reflect reality in their sheer absolutism. Scientific research found that there are indeed many security advantages of Free, Open Source Software both theoretically as well as practically, however only under certain conditions. Free Open Source Software is neither more or less secure per sé, but it does have the potential to be more transparent and secure if utilised carefully.

For one, the software supply chain is a big issue both for Open Source and proprietary software projects, which needs to be addressed. For users, that means that they have to be informed about the development and maintenance status of the software they use as well as its dependencies. This is true for Free as well as non-free software.

Secondly, the Open Source community needs to realise that temporary secrecy can be of benefit when it comes to the disclosure of vulnerabilities, without betraying their transparent nature. Many security critical projects have taken measures towards this in the past two decades and ask for vulnerabilities to be reported through secure channels directly to the core development team. Vulnerabilities reported in such ways are typically addressed within few hours or days and appropriate security updates made available to everyone along with the public disclosure of these issues. This fosters both a relationship of trust as well as reasonable handling of security incidences between developers and users.

All in all, a license obviously does not inherently make software more secure. It always depends on the passion of software developers as well as the amount of knowledge people that take care of a project. However, Free, Open Source Software (FOSS) is outstandinly open and transparent about development and security measures, whereas with proprietary software, users have to trust vendors about the status and effort that goes into a certain release. It is therefore safe to say, that through its transparency FOSS has a theoretical as well as practical advantage over proprietary software not only in terms of privacy (as is a broad consesus), but also when it comes to software and data security.

Sources

- Wilander J. (2021): Is Open Source More Secure Than Cloused Source? Online at https://devops.com/is-open-source-more-secure-than-closed-source/

- Vlad V., Maryna Z. (2021): Three Myths Debunked About Open Source Software Security. Online at https://rubygarage.org/blog/open-source-software-security

- Deutsche Bundesregierung (2017): Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Dr. Konstantin von Notz, Renate Künast, Tabea Rößner, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN. Drucksache 18/12471. Online unter https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/18/129/1812906.pdf

- Scarfone K., Jansen W. & Tracy M. (2008): Guide to General Server Security. National Institute of Standards and Technology. URL: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/SP/nistspecialpublication800-123.pdf

- King B. (2017): Is Security Through Obscurity Safer Than Open Source Software?. Online at https://www.makeuseof.com/tag/security-obscurity-open-source-better/

- Nextcloud-Team (2022): Nextcloud developer documentation. URL: https://docs.nextcloud.com/server/latest/developer_manual/

- Das A. (2021): Is Open-Source Software Secure? Online at https://news.itsfoss.com/open-source-software-security/

- Walker J. M. (2016): Open source and the software supply chain. Online at https://opensource.com/article/16/12/open-source-software-supply-chain

- Swire P. (2004): A Model for When Disclosure Helps Security: What Is Different About Computer and Network Security? Journal on Telecommunications and High Technology Law 163(3). URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.531782

- Swire P. (2006): A Theory of Disclosure for Security and Competitive Reasons: Open Source, Proprietary Software, and Government Agencies. Houston Law Review 101), Ohio State Public Law Working Paper No. 49, URL: https://ssrn.com/abstract=842228

- Ransbotham S. (2010): An Empirical Analysis of Exploitation Attempts based on Vulnerabilities in Open Source Software. Workshop on the Economics of Information Security. URL: https://infosecon.net/workshop/downloads/2010/pdf/An_Empirical_Analysis_of_Exploitation_Attempts_based_on_Vulnerabilities_in_Open_Source_Software.pdf

- Schryen G. (2009). Security of Open Source and Closed Source Software: An Empirical Comparison of Published Vulnerabilities. AMCIS. URL: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Security-of-Open-Source-and-Closed-Source-Software%3A-Schryen/fde3ba053cede0e7fde6e220d6d09e42638421d5

- Zahedi M., Babar M., Treude C. (2018): An Empirical Study of Security Issues Posted in Open Source Projects. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS). URL: https://www.academia.edu/35153562/An_Empirical_Study_of_Security_Issues_Posted_in_Open_Source_Projects

Jan is co-founder of ViOffice. He is responsible for the technical implementation and maintenance of the software. His interests lie in particular in the areas of security, data protection and encryption.

In addition to his studies in economics, later in applied statistics and his subsequent doctorate, he has years of experience in software development, open source and server administration.